Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot | |

|---|---|

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot | |

| Born | 26 February 1725 |

| Died | 2 October 1804 (aged 79) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Children | 2 children |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | fardier à vapeur |

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot (26 February 1725 – 2 October 1804) was a French inventor who built the world's first full-size and working self-propelled mechanical land-vehicle, the "Fardier à vapeur" – effectively the world's first automobile.[1][a]

Background

[edit]He was born in Void-Vacon, Lorraine, (now department of Meuse), France. He trained as a military engineer. In 1765, he began experimenting with working models of steam-engine-powered vehicles for the French Army, intended for transporting cannons.

First self-propelled vehicle

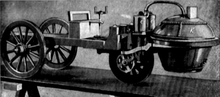

[edit]French Army captain Cugnot was one of the first to successfully employ a device for converting the reciprocating motion of a steam piston into a rotary motion by means of a ratchet arrangement. A small version of his three-wheeled fardier à vapeur ("steam dray") was made and used in 1769 (a fardier was a massively built two-wheeled horse-drawn cart for transporting very heavy equipment, such as cannon barrels)

In 1770, a full-size version of the fardier à vapeur was built, specified to be able to carry four tons and cover two lieue (7.8 km, or 4.8 miles) in one hour, a performance it never achieved in practice. The vehicle weighed about 2.5 tonnes tare, and had two wheels at the rear and one in the front where the horses would normally have been. The front wheel supported a steam boiler and driving mechanism. The power unit was articulated to the "trailer", and was steered from there by means of a double handle arrangement. One source states that it seated four passengers and moved at a speed of 3.6 kilometres per hour (2.25 mph).[3]

The vehicle was reported to have been very unstable owing to poor weight distribution, a serious disadvantage for a vehicle intended to be able to traverse rough terrain and climb steep hills. In addition, boiler performance was also particularly poor, even by the standards of the day. The vehicle's fire needed to be relit, and its steam raised again, every quarter of an hour or so, which considerably reduced its overall speed and distance.

After running a small number of trials, variously described as being between Paris and Vincennes and at Meudon, the project was abandoned. This ended the French Army's first experiment with mechanical vehicles. Even so, in 1772, King Louis XV granted Cugnot a pension of 600 livres a year for his innovative work, and the experiment was judged interesting enough for the fardier to be kept at the arsenal. In 1800 it was transferred to the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, where it can still be seen today.

241 years later, in 2010, a copy of the "fardier de Cugnot" was built by students from ParisTech, in conjunction with Cugnot's native commune of Void-Vacon. This replica worked perfectly, demonstrating the validity of the concept and the veracity of the tests carried out in 1769.[4] The replica was exhibited at the 2010 Paris Motor Show before returning for exhibit in Void-Vacon.[5]

First automobile accident

[edit]

There are reports of a minor incident in 1771, when the second prototype vehicle is said to have accidentally knocked down a brick or stone wall, either that of a Paris garden or part of the Paris Arsenal walls, in perhaps the first known automobile accident.[6] The incident is unrecorded in contemporary accounts, first appearing in 1804, thirty-three years after the alleged accident. Nevertheless, the story persists that Cugnot was arrested and convicted of dangerous driving, another first for him if true.[7]

Later life

[edit]Following the French Revolution, Cugnot's pension was withdrawn in 1789 and he went into exile in Brussels where he lived in poverty. Shortly before his death, Cugnot's pension was restored by Napoleon Bonaparte and he eventually returned to Paris where he died on 2 October 1804.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ It has alternatively been suggested that the earliest self-propelled vehicle was designed in about 1672 by Ferdinand Verbiest, a member of a Jesuit mission in China, but that it was too small to carry a driver and may have never been built or have worked.[2]

Citations

- ^ "Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot | Facts, Invention, & Steam Car | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "1679–1681 – R P Verbiest's Steam Chariot". History of the Automobile: origin to 1900. Hergé. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ L. A. Manwaring, The Observer's Book of Automobiles (12th ed.) 1966, Library of Congress catalog card # 62-9807. p. 7

- ^ "Fardier de Cugnot – 1770 – France". tbauto.org. Tampa Bay Automobil Museum. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Notre fardier devant le monument Cugnot à Void-Vacon (Meuse), on the site of lefardierdecugnot.fr

- ^ Mastinu & Ploechl (2014), p. 1584.

- ^ "Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot". The Motor Museum in Miniature. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Mastinu, Gianpiero; Ploechl, Manfred, eds. (2014). Road and Off-Road Vehicle System Dynamics Handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-0490-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Max J. B. Rauck, Cugnot, 1769-1969: der Urahn unseres Autos fuhr vor 200 Jahren, München: Münchener Zeitungsverlag, 196

- Bruno Jacomy, Annie-Claude Martin: Le Chariot à feu de M. Cugnot, Paris, 1992, Nathan/Musée national des techniques, ISBN 2-09-204538-5.

- Louis Andre: Le Premier accident automobile de l'histoire, in La Revue du Musée des arts et métiers, 1993, Numéro 2, p 44-46

External links

[edit]- The fardier exhibit at the Musee National des Arts et Métiers:

- Catalogue entry, with specifications Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Detail images of exhibit Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Additional reference sources Archived 13 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Cugnot on 3wheelers.com

- Link to downloadable video at DB Museum, showing a reconstruction of the fardier in action (B&W)

- Replica at the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum

- Hybrid-Vehicle.org: The Steamers Archived 25 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Le fardier de Cugnot: page in French about Cugnot and his invention, hosted at an Île-de-France regional government web site and credited to the Société des ingénieurs de l'automobile (Society of Automotive Engineers).

- Biography of Cugnot from 'World of Invention'