Otto Ohlendorf

Otto Ohlendorf | |

|---|---|

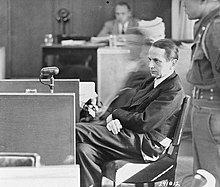

Mugshot for the Nuremberg Military Tribunal (1 March 1948) | |

| Born | 4 February 1907 |

| Died | 7 June 1951 (aged 44)[a] |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Conviction(s) | Crimes against humanity War crimes Membership in a criminal organization |

| Trial | Einsatzgruppen trial |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 90,000+ |

Span of crimes | June 1941 – July 1942 |

| Country | Ukraine and Russia |

| Target(s) | Slavs, Jews, Romas, and Communists |

Date apprehended | 23 May 1945 |

| SS career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Rank | SS-Gruppenführer |

| Commands |

|

Otto Ohlendorf (German pronunciation: [ˈɔtoː ˈʔoːləndɔʁf]; 4 February 1907 – 7 June 1951) was a German SS functionary and Holocaust perpetrator during the Nazi era. An economist by education, he was head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) Inland, responsible for intelligence and security within Germany. In 1941, Ohlendorf was appointed the commander of Einsatzgruppe D, which perpetrated mass murder in Moldova, south Ukraine, the Crimea and, during 1942, the North Caucasus. He was tried at the Einsatzgruppen Trial, sentenced to death, and executed by hanging in 1951.

Life and education

[edit]Born in Hoheneggelsen (today part of Söhlde; then in the Kingdom of Prussia), Otto Ohlendorf came into the world as part of "a farming family".[2] He joined the Nazi Party in 1925 and the SS in 1926.[3] Ohlendorf studied economics and law at the University of Leipzig and the University of Göttingen, and by 1930 was already giving lectures at several economic institutions. In 1931, Ohlendorf was awarded a two-semester scholarship to the University of Pavia.[4] According to historian Alan Steinweis, Ohlendorf was one of the few Nazis who possessed two doctoral degrees.[5] In 1933 he obtained the position of a research directorship in the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.[3] Ohlendorf was active in the National Socialist Students' League in both Kiel and Göttingen and taught at the Nazi Party's school in Berlin.[6] He participated in major debates between the SS, the German Labour Front, and the Quadrenniel Organization on economic policy.[7] By 1938 he was also manager in the Trade section of the Reich Business Board (Reichswirtschaftskammer). Historian Christian Ingrao quips that for Ohlendorf, Nazism was a "quest for race" in the historical continuum, and even though he never stated it that way, his faith in Germandom was akin to that of his fellow SS intellectuals.[8]

SS career

[edit]

Ohlendorf joined the SD in 1936 and became an economic consultant of the organisation. Like other academics such as Helmut Knochen and Franz Six, Ohlendorf had been recruited by SD talent-scouts.[9] Attached to the SS with the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer, by 1939 he had reached the rank of SS-Standartenführer and was appointed as head of Amt III (SD-Inland) of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA),[10][11] a position he kept until 1945.[6] His role in collecting intelligence from his secret-police agents was disliked by some of the Nazi leadership. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler once characterized Ohlendorf as "an unbearable Prussian" who was "without humour".[6] Nonetheless, Ohlendorf was instrumental as a member of the SD in shaping Nazi economic doctrine, which became "increasingly virulent as the war progressed" as he attempted to mould the economy "in an ethnic context".[12] It was Ohlendorf's responsibility as head of the SD-Inland to collect data and scientifically to examine social, cultural, and economic issues, assembling reports to his superiors in the Nazi government.[13] Routine public-opinion surveys—which were under the purview of Ohlendorf and of SS-Major Reinhard Höhn—constituted some of these reports.[14] These public-opinion polls on the social climate of Nazi Germany were both unpopular and controversial.[15]

In June 1941, Reinhard Heydrich appointed Ohlendorf as commander of Einsatzgruppe D,[16] which operated in southern Ukraine and Crimea.[17] Joining the Einsatzgruppen was an unappealing prospect and Ohlendorf refused twice before his eventual appointment.[18] Transfers from the RSHA to the Einsatzgruppen were in part due to personnel shortages but also to keep the initial killing-operations confined to those who already knew the details, such as Ohlendorf, Arthur Nebe, and Paul Blobel.[19] Einsatzgruppe D was the smallest of the task forces, but was supplemented by Romanians along their way through the killing fields of Bessarabia, southern Ukraine, and the Caucasus.[20] Additional manpower for Einsatzgruppe D came from Ukrainian auxiliary-police formations.[21] Supporting military operations, Ohlendorf's group was attached to the Eleventh Army.[22][b] Ohlendorf's Einsatzgruppe in particular was responsible for the 13 December 1941 massacre at Simferopol, where at least 14,300 people, mostly Jews, were killed. Over 90,000 murders throughout Ukraine and the Caucasus are attributed to Ohlendorf's unit.[24][c]

Ohlendorf disliked the use of the oft-employed Genickschuß (shot to the back of the neck) and preferred to line up victims and fire at them from a greater distance so as to alleviate personal responsibility for individual murders.[25] All forms of contact between the firing squads and victims were limited—per Ohlendorf's insistence—until the last moments before the killing started, and up to three rifleman were allocated to each person about to be shot.[26] To ensure the group-killing mentality, Ohlendorf forbade any commando from taking individual actions and explicitly instructed his men not to take any of the victims' valuables.[27] One of Ohlendorf's most trusted "proper" military-style murderers, SS-Haupsturmführer Lothar Heimbach, once exclaimed, "A man is the lord over life and death when he gets an order to shoot three hundred children—and he kills at least one hundred fifty himself."[28][d]

Many of the killing operations were personally overseen by Ohlendorf, who wanted to ensure they were "military in character and humane under the circumstances".[30] The number of persons killed under the leadership of Einsatzgruppen commanders such as Ohlendorf are "staggering", despite the use of varying murder techniques.[31] On 1 August 1941, Einsatzgruppen commanders, including Ohlendorf, received instructions from Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller to keep headquarters (Hitler especially) informed of their progress in the East; Müller also encouraged the speedy delivery of photographs showing the results of these operations.[32] During September 1941, Ohlendorf's group slaughtered 22,467 Jews and communists at Mykolaiv near the Black Sea port of Odesa.[33]

Due to the Wehrmacht's insistence that Ukraine's agricultural production was needed to sustain its military campaign, Ohlendorf was asked by the army during October 1941 to refrain from killing some of the Jewish farmers[e]—a request he honored—but one which earned him Himmler's contempt.[f] Nonetheless, just a month prior in September 1941, Ohlendorf announced to his men that "from now on the Jewish question is going to be solved and that means liquidation".[35] From that month forward, the Einsatzgruppen had begun the process of systematically shooting not just men but women and children, a transition that historian Peter Longerich terms "the decisive step on the way towards a policy of racial annihilation".[36]

Between February and March 1942, Himmler ordered that gas vans should be used to murder women and children so as to reduce the strain on the men, but Ohlendorf reported that many of the Einsatzkommandos refused to utilize the vans since burying the victims proved an "ordeal" afterwards.[37][g] Gas-van killing operations were usually conducted at night to keep the population from witnessing the macabre affair.[39] After the victims' deaths, Jewish Sonderkommandos were forced to unload the bodies, clean the excrement from inside the van's gas chamber, and once the clean-up was complete, were themselves immediately shot.[40] As far as Ohlendorf was concerned, the gas vans were impracticable for the scale of killing demanded by Himmler; namely, since they could only kill between fifteen and twenty-five persons at a time.[41]

Historian Donald Bloxham characterises Ohlendorf as a bureaucrat who was trying to "prove himself in the field".[42] Another historian, Mark Mazower, describes Ohlendorf as a "gloomy, driven, self-righteous Prussian".[43] His commitment to the Nazi cause kept him in Ukraine longer than any of his comrades, and while he may have disliked the political direction in which Germany was headed, he never registered complaints about murdering Jews.[43] He did, however, express misgivings about the barbarity and sadism being meted out by the Romanian units that accompanied the Einsatzgruppen in their murderous tasks, since they were not only leaving a trail of corpses in their wake, they were also pillaging and raping in the process.[44] He also complained about the Romanians driving thousands of frail elderly persons and children from Bessarabia and Bokovina—all incapable of work—into German-held regions, whom Ohlendorf's men forced back into Romanian territory, but not without killing a significant percentage of them as a result.[45]

Ohlendorf devoted only four years (1939–1943) of full-time activity to the RSHA, for in 1943, in addition to his other jobs, he became a deputy director-general (German: Staatssekretär) in the Reich Ministry of Economic Affairs (German: Reichswirtschaftsministerium).[46] Sometime in November 1944, he was promoted to SS–Gruppenführer.[3] Believing their expertise invaluable, Ohlendorf, Ludwig Erhard, and other experts concerned themselves with how to stabilize German currency after the prospective end of the war.[47] Hoping to salvage the reputation of the SD, Ohlendorf offered his services in the hopes that he could shape the postwar reconstruction of Germany, but along "National Socialist lines", remaining convinced—as was Admiral Karl Dönitz (who would make Ohlendorf his de facto economics minister under Albert Speer in the Flensburg Government of May 1945)—that some form of Nazism would ultimately survive.[48][h]

In May 1945, Ohlendorf participated in Himmler's flight from Flensburg. He and several other subordinates were arrested by the British near Lüneburg on 23 May 1945.[50][51] Himmler committed suicide shortly after being captured.[52] For several weeks after his arrest, Ohlendorf was carefully interrogated, during which he revealed the criminal nature of the German campaign in the East.[53]

Nuremberg trials

[edit]

Ohlendorf was called as a witness by the prosecution during the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg on 3 January 1946. During the subsequent Einsatzgruppen trial, Ohlendorf was the chief defendant, and was also a key witness in the prosecution of other indicted war criminals. Ohlendorf's apparently reliable testimony was attributed to his distaste for the corruption in Nazi Germany and a stubborn commitment to duty. The court examined Ohlendorf concerning Einsatzgruppen operations in particular.[54] At his trial, Ohlendorf insisted that he, as a loyal Nazi, had acted properly and done nothing wrong.[55] He expressed no remorse for his actions, telling prosecutor Ben Ferencz, who was Jewish, afterwards that the Jews of America would suffer for what Ferencz had done. He seemed more concerned about the moral strain on those carrying out the murders than those being murdered.[56] Ohlendorf attempted to present Einsatzgruppen operations in the Soviet area "not as a racist programme for the annihilation of all the Jews ... but as a general liquidation order primarily aimed at 'securing' the newly won territory."[57] Defending his actions, Ohlendorf compared Einsatzgruppen activities to the Biblical Jewish extirpation of its enemies; he likewise claimed that his firing squads were "no worse than the 'press-button killers' who dropped the atom bomb on Japan."[58]

Ohlendorf's defense also claimed that Hitler had ordered the murder of all Jews before the German invasion of the Soviet Union. This order was revealed to be a fabrication many years later by historian Alfred Streim.[59] According to Erwin Schulz, one of only two of Ohlendorf's codefendants to not attest to his version of events, he only received such an order in mid-August 1941. Unlike Ohlendorf, however, Schulz, unwilling to kill women and children, had refused to carry out this order and was promptly sent back to Germany. Schulz's initial orders had been more vague and meant to tacitly encourage the Einsatzgruppen to carry out a campaign of extermination, without saying it outright.[60]

Prior to the invasion, Schulz testified that Heydrich had told him:

"That every one should be sure to understand that, in this fight, Jews would definitely take their part and that, in this fight, everything was set at stake, and the one side which gave in would be the one to be overcome. For that reason, all measures had to be taken against the Jews in particular. The experience in Poland had shown this."[60]

Ohlendorf justified the systematic murder as anticipatory self-defense against the mortal threat supposedly posed by Jews, Romas, Communists, and others. He argued that the killing of Jewish children was necessary since they would have grown up to hate Germany.[56] The term he used, "permanent security", was later borrowed by historian A. Dirk Moses in his criticism of the concept of genocide as a category mistake. Moses argues that permanent security is an unobtainable goal that if pursued, inevitably leads to anticipatory attacks that harm civilians, and therefore it "underlies all atrocity crimes and common state practices like aerial bombing and sanctions."[61]

Despite his attempts to establish moral equivalency for atrocities upon the Allies, Otto Ohlendorf was convicted of crimes against humanity and war crimes committed during World War II. He was sentenced to death in April 1948 and spent three years in detention before being hanged at the Landsberg Prison in Bavaria on 7 June 1951.[3][58]

References

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ "Five death sentences were confirmed: the sentence against Oswald Pohl, as well as those passed against the leaders of the Mobile Killing Units, Paul Blobel, Werner Braune, Erich Neumann, and Otto Ohrlendorf...In the early morning hours of 7 June, the Nazi criminals were hanged in the Landsberg prison courtyard."[1]

- ^ One task which Ohlendorf disdained was providing guards for the harvest at the behest of Army commanders, who wanted to prevent the Romanians from consuming any of the goods.[23]

- ^ During the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg, Ohlendorf stated that he tried to mitigate any "unnecessary agitation" for the victims.[3]

- ^ Justifying the murder of children, Ohlendorf stated, "the children were people who would grow up and surely being the children of parents who had been killed, they would constitute a danger no smaller than their parents."[29]

- ^ In agreement with the army,' Ohlendorf testified at his trial, "we had excluded from the executions a large number of Jews - the farmers. The Wehrmacht had wanted to make sure agricultural production would continue in the Ukraine, Russia's breadbasket, to sustain further campaigns."[34]

- ^ Ohlendorf complained about this, stating: "Himmler was incensed to learn that the Jewish farmers had been spared. [...] I was reproached for this measure.[34]

- ^ Historian Martin Gilbert reported that in front of the Nuremberg tribunal, Ohlendorf described the use of gas vans for killing operations as "unpleasant" and that the Einsatzkommandos disliked dealing with the bodies.[38]

- ^ According to Volker Ulllrich,"It was considered a given that Speer would be part of the new government [under Dönitz in Flensburg]. [...] Now Speer was up for the post of economics and production minister. [...] Otto Ohlendorf, however, was the man who was actually supposed to run the economics ministry. [...] Ohlendorf had been a ministerial director and deputy state secretary in the economics ministry under Walther Funk. In this capacity, his duties included planning for the postwar economy, which no doubt qualified him in Speer's eyes for his new job in Flensburg. [...] Ohlendorf was not content to offer his services as an economic expert, and he proposed to Dönitz that personnel from the Reich Main Security Office that had moved with him to the 'northern realm' could serve as the basis for a new German intelligence body."[49]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Frei 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Stackelberg 2007, p. 228.

- ^ a b c d e Zentner & Bedürftig 1991, p. 665.

- ^ Capani 2017, p. 77.

- ^ Steinweis 2023, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Wistrich 1995, p. 184.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Burleigh 2000, p. 186.

- ^ Evans 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Rozett & Spector 2009, p. 345.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 143.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 308.

- ^ Arad 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Koch 1985, p. 383.

- ^ Langerbein 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Burleigh 2000, p. 620.

- ^ Cesarani 2016, p. 387.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Burleigh 2000, p. 624.

- ^ Chapoutot 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 126.

- ^ Weale 2012, p. 319.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 166.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 127.

- ^ Botwinick 2001, pp. 184–188.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 122.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 172.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2003, p. 182.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 228.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 252.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 243.

- ^ Gilbert 1985, p. 365.

- ^ Langerbein 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Langerbein 2003, p. 116.

- ^ Shirer 1990, pp. 960–961.

- ^ Bloxham 2009, p. 267.

- ^ a b Mazower 2008, p. 254.

- ^ Mazower 2008, p. 336.

- ^ Evans 2010, p. 234.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 104.

- ^ Janich 2013, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Mazower 2008, pp. 532–533.

- ^ Ullrich 2021, p. 101.

- ^ Rhodes 2003, p. 272.

- ^ Goda 2016.

- ^ Manvell & Fraenkel 1987, pp. 244–248.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, p. 227.

- ^ Cesarani 2016, p. 784.

- ^ Chapoutot 2018, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Ferencz (1946–1949).

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 186.

- ^ a b Wistrich 1995, p. 185.

- ^ Birn & Rapp 2011, pp. 475–479.

- ^ a b N.M.T. (1945). "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals" (PDF direct download). Volume IV : "The Einsatzgruppen Case" complete, 1210 pages. Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10. pp. 542–543 in PDF (518–519 in original document). Retrieved 1 March 2015.

With N.M.T. commentary to testimony of Erwin Schulz (pp. 165–167 in PDF).

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 16–17, 27.

Bibliography

[edit]- Arad, Yitzhak (2009). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. Lincoln and Jerusalem: University of Nebraska Press. ASIN B01JXSISSU.

- Birn, R. B.; Rapp, W. H. (1 May 2011). "Introductory Note". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 9 (2): 475–479. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqr013.

- Bloxham, Donald (2009). The Final Solution: A Genocide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19955-034-0.

- Botwinick, Rita Steinhardt (2001). A History of the Holocaust: From Ideology to Annihilation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13011-285-9.

- Burleigh, Michael (2000). The Third Reich: A New History. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-80909-325-0.

- Capani, Jennifer (2017). An 'Alter Kampfer' at the Forefront of the Holocaust: Otto Ohlendorf Between Careerism and Nazi Fundamentalism. New York: St. John's University – Theses and Dissertations. 5.

- Cesarani, David (2016). Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews, 1933–1945. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-25000-083-5.

- Chapoutot, Johann (2018). The Law of Blood: Thinking and Acting as a Nazi. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67466-043-4.

- Evans, Richard (2010). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14311-671-4.

- Ferencz, Benjamin B. "Story 34—Mass Murderers Seek to Justify Genocide (1946–1949)". Benny Stories. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Frei, Norbert (2002). Adenauer's Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23111-882-8.

- Gilbert, Martin (1985). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe during the Second World War. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-0348-7.

- Goda, Norman (2016). "Report on the Otto Ohlendorf IRR File". National Archives. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 0-8419-0910-5.

- Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, MA: Polity. ISBN 978-0-74566-026-4.

- Janich, Oliver (2013). Die Vereinigten Staaten von Europa: Geheimdokumente enthüllen: Die dunklen Pläne der Elite (in German). München: FinanzBuch Verlag. ASIN B00CWPY50C.

- Koch, H.W. (1985). "Part IV: Introduction". In H.W. Koch (ed.). Aspects of the Third Reich. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-33335-273-1.

- Langerbein, Helmut (2003). Hitler's Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-285-0.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Manvell, Roger; Fraenkel, Heinrich (1987). Heinrich Himmler. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85367-740-3.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. New York; Toronto: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59420-188-2.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2023). "Genocide as a Category Mistake: Permanent Security and Mass Violence Against Civilians". In Frank Jacob; Kim Sebastian Todzi (eds.). Genocidal Violence: Concepts, Forms, Impact. Genocide and Mass Violence in the Age of Extremes. Vol. 6. De Gruyter Oldenbourg. pp. 15–38. ISBN 978-3-11-078132-8.

- Rhodes, Richard (2003). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-37570-822-0.

- Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (2009). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Jerusalem: JPH. ISBN 978-0-81604-333-0.

- Shirer, William (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 978-1-56731-163-1.

- Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41530-861-8.

- Steinweis, Alan E. (2023). The People's Dictatorship: A History of Nazi Germany. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-00932-497-7.

- Ullrich, Volker (2021). Eight Days in May: How Germany's War Ended. Translated by Chase, Jefferson. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14199-411-6. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- Weale, Adrian (2012). Army of Evil: A History of the SS. New York: Caliber Printing. ISBN 978-0451237910.

- Wistrich, Robert (1995). Who's Who In Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41511-888-0.

- Zentner, Christian; Bedürftig, Friedemann (1991). The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. New York: MacMillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-897500-6.

External links

[edit]- Newspaper clippings about Otto Ohlendorf in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- "Otto Ohlendorf, Einsatzgruppe D, and the ‘Holocaust by Bullets’," 13 January 2021 biographical article by Jason Dawsey (National World War II Museum, New Orleans, LA)

- 1907 births

- 1951 deaths

- Einsatzgruppen personnel

- Executed German mass murderers

- Executed military leaders

- Executions by the United States Nuremberg Military Tribunals

- German people convicted of crimes against humanity

- German prisoners of war in World War II held by the United Kingdom

- Holocaust perpetrators in Russia

- Holocaust perpetrators in Ukraine

- Lawyers in the Nazi Party

- People from Hildesheim (district)

- People from the Province of Hanover

- Reich Security Main Office personnel

- SS-Gruppenführer

- Witnesses to the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg