First Battle of Gaza

| First Battle of Gaza | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

Ottoman officers who successfully defended Gaza during the first battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 31,000 | 19,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

523 killed 2,932 wounded 512 missing |

| ||||||

The First Battle of Gaza was fought on 26 March 1917 during the first attempt by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), which was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War. Fighting took place in and around the town of Gaza on the Mediterranean coast when infantry and mounted infantry from the Desert Column, a component of the Eastern Force, attacked the town. Late in the afternoon, on the verge of capturing Gaza, the Desert Column was withdrawn due to concerns about the approaching darkness and large Ottoman reinforcements. This British defeat was followed a few weeks later by the even more emphatic defeat of the Eastern Force at the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917.

In August 1916, the EEF victory at Romani ended the possibility of land-based attacks on the Suez Canal, first threatened in February 1915 by the Ottoman Raid on the Suez Canal. In December 1916, the newly created Desert Column's victory at the Battle of Magdhaba secured the Mediterranean port of El Arish and the supply route, water pipeline and railway stretching eastwards across the Sinai Peninsula. In January 1917, the victory of the Desert Column at the Battle of Rafa completed the capture of the Sinai Peninsula and brought the EEF within striking distance of Gaza.

Two months later, in March 1917, Gaza was attacked by Eastern Force infantry from the 52nd (Lowland) Division reinforced by an infantry brigade. This attack was protected from the threat of Ottoman reinforcements by the Anzac Mounted Division and a screen from the Imperial Mounted Division. The infantry attack from the south and southeast on the Ottoman garrison in and around Gaza was strongly resisted. While the Imperial Mounted Division continued to hold off threatening Ottoman reinforcements, the Anzac Mounted Division attacked Gaza from the north. They succeeded in entering the town from the north, while a joint infantry and mounted infantry attack on Ali Muntar captured the position. However, the lateness of the hour, the determination of the Ottoman defenders, and the threat from the large Ottoman reinforcements approaching from the north and north east resulted in the decision by the Eastern Force to retreat. It has been suggested that this move snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

Background

[edit]

As the Allied operations in the Middle East were secondary to the Western Front campaign, reinforcements requested by General Sir Archibald Murray, commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), were denied. Further, on 11 January 1917, the War Cabinet informed Murray that large scale operations in Palestine were to be deferred until September, and he was informed by Field Marshal William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, that he should be ready to send possibly two infantry divisions to France. One week later, Murray received a request for the first infantry division and dispatched the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division. He was assured that none of his mounted units would be transferred from the EEF, and was told "that there was no intention of curtailing such activities as he considered justified by his resources."[1][2] Murray repeated his estimate that five infantry divisions, in addition to the mounted units, were needed for offensive operations.[3]

After 26 February 1917, when an Anglo-French Congress at Calais decided on a spring offensive, Murray received strong encouragement. The decision by the Supreme War Council was given increased impetus for "Allied activity" on 8 March when the Russian Revolution began. By 11 March Baghdad in Mesopotamia had been occupied by British Empire forces, and an offensive in Macedonia had been launched. In April the Battle of Arras was launched by the British, and the French launched the Nivelle offensive.[4] Britain's three major war objectives now were to maintain maritime supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea, while preserving the balance of power in Europe and the security of Egypt, India, and the Persian Gulf. The latter could be secured by an advance into Palestine and the capture of Jerusalem. A further advance would ultimately cut off the Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia from those on the Arabian Peninsula and secure the region.[5]

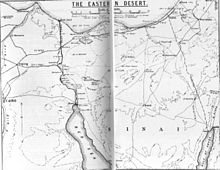

By 5 February the water pipeline from the Egyptian Sweet Water Canal, which carried water from the Nile, had reached El Arish, while the railway line was being laid well to the east of that place. The creation of this infrastructure enabled a strong defensive position and a forward base to be established at El Arish.[6] There were now two possible directions for an advance towards Jerusalem by Eastern Force to take: through Rafa on the coast, or inland through Hafir El Auja, on the Ottoman railway. Lieutenant General Charles Macpherson Dobell, commanding Eastern Force, thought that an advance along the coast could force the Ottoman Army to withdraw their inland forces, as they became outflanked and subject to attack by the EEF from the rear. He proposed keeping two divisions at El Arish, moving his headquarters there, while his mounted division would advance to reoccupy Rafa (captured by the Desert Column on 9 January during the Battle of Rafa).[3]

With the 11 January War Cabinet decision reversed by the 26 February Congress, the EEF was now required to capture the stronghold of Gaza as a first step towards the capture of Jerusalem.[5] The town was one of the most ancient cities in the world, being one of five cities of the Palestine Alliance, which had been fought over many times during its 4,000-year history.[7] By 1917 Gaza had an important depot for cereals with a German steam mill. In the area barley, wheat, olives, vineyards, orange groves, and wood for fuel were grown, as well as the grazing of many goats. Barley was exported to England for brewing into beer. Maize, millet, beans, and watermelon were cultivated in most of the surrounding localities, and harvested in early autumn.[8][9][10]

Mounted units reorganised

[edit]A pause in the EEF's advance was necessary to enable the lines of communication to be lengthened and strengthened. While this work was being carried out, the mounted brigades were reorganised into two mounted divisions.[11][12] This was prompted by the arrival of the 6th Mounted Brigade and 22nd Mounted Brigade from the Salonika campaign. Instead of grouping the two new mounted brigades with the 5th Mounted Brigade to form a new Imperial Mounted Division, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was transferred from the Anzac Mounted Division to the new division, and replaced by the 22nd Mounted Brigade. The Imperial Mounted Division, established 12 February 1917 at Ferry Post on the Suez Canal under the command of Major General Henry West Hodgson, was established with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade and 4th Light Horse Brigade (which was in the process of formation at Ferry Post and was scheduled to leave for the front on 18 March) along with the 5th and 6th Mounted Brigades.[13][14][15] Within Dobell's Eastern Force, General Philip Chetwode commanded the Desert Column, which included the Anzac Mounted Division, the partly formed Imperial Mounted Division, and the 53rd (Welsh) Division of infantry.[2] After the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division left for the Western Front, Dobell's Eastern Force consisted of four infantry divisions; the 52nd (Lowland) Division, the 53rd (Welsh) Division, the 54th (East Anglian) Division and the 74th (Yeomanry) Division, which had recently been formed by converting yeomanry regiments into infantry battalions.[2]

EEF raid on Khan Yunis

[edit]

Dobell thought the victory at Rafa should be quickly exploited by attacking Gaza; "an early surprise attack was essential ... otherwise it was widely believed the enemy would withdraw without a fight."[16][17] He ordered Rafa to be occupied by mounted troops while two infantry divisions of Eastern Force remained at El Arish to defend his headquarters.[3]

On 23 February, the Anzac Mounted Division and the 53rd (Welsh) Division, commanded by Major General S.F. Mott, were camped on the beach at Sheikh Zowaiid. Here they were joined by the 22nd Mounted Brigade, replacing the 5th Mounted Brigade which returned to El Burj.[18] That day, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the 2nd Light Horse Brigades commanded by Edward Chaytor made a reconnaissance in force to Khan Yunis 5 miles (8.0 km) past Rafa. Khan Yunis was held in strength, and the Chaytor's Column withdrew after "a brush" with the defenders. The town was found to be part of a line of strong posts held by the Ottoman Army protecting southern Palestine. Known as the Hans Yonus–El Hafir line, these posts consisted of well-dug trenches. They were located at Shellal, which was a particularly strongly fortified position, at Weli Sheikh Nuran, at Beersheba, and at Khan Yunis.[6][19]

As a consequence of the reconnaissance to Khan Yunis, and the growing strength of EEF units in the area, the Ottoman Army garrisons realised the line was nevertheless too weak to be successfully defended. In February, Enver Pasha, Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, and Cemal Pasha withdrew from the line, retiring 14 miles (23 km) northwards. Here they established much more formidable defences in front of Gaza, to stop any Allied advance up the coast. This withdrawal was completed by mid–March when the Ottoman Fourth Army was in position.[20][21][22][23] Their new defensive line stretched north and north east, from Gaza on the north side of the Wadi Ghuzzee to Tel esh Sheria, where the Palestine railway crossed the Wadi esh Sheria.[23][24]

On 28 February, Chetwode's Desert Column occupied Khan Yunis unopposed and the headquarters of the Column was established at Sheikh Zowaiid, while Eastern Force headquarters remained at El Arish.[6] The ancient town of Khan Yunis on the main road to Gaza was said to be the birthplace of Delilah. With bazaars, narrow streets and a castle, it was one of several villages in this fertile area of southern Palestine, 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Rafa and the Egyptian–Ottoman frontier. Here was found the largest and deepest well in the area, and after engineers had installed a pumping machine, it gave an unlimited supply of water for both men and horses. The village quickly became an important forward site for supply depots and bivouacs.[8][25] Around Khan Yunis gardens, orange orchards, fig plantations and grazing were carried on by the local population, while in the Rafa and Sheikh Zowaiid areas barley and wheat were grown.[8][9][10]

The area across the border ... was "delightful country, cultivated to perfection and the crops look quite good if not better than most English farms, chiefly barley and wheat. The villages were very pretty – a mass of orange, fig and other fruit trees ... The relief of seeing such country after the miles and miles of bare sand was worth five years of a life."

— Lieutenant Robert Wilson[26]

EEF aerial bombing

[edit]A series of bombing raids on the railway from Junction Station to Tel el Sheria aimed to disrupt the Ottoman lines of communication during the build-up to the battle. No. 1 Squadron Australian Flying Corps and No. 14 Squadron bombed Beersheba in mid February, destroying 3 German planes, and on 25 February assisted a French battleship's shelling of Jaffa, by directing the ship's fire. On the same day, the German aerodrome at Ramleh was bombed. Then on 5 March six aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) conducted bombing attacks intended to interfere with the Ottoman withdrawal from the Khan Yunis line. They bombed Beersheba and the Palestine railway at Tel esh Sheria 12 miles (19 km) to the northwest. Although the damage was not great, the railway at Tel esh Sheria continued to be bombed in moonlight on 7 March, by relays of aircraft. Junction Station and supply depot, an important junction of southern Palestine railways with the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway many miles to the north, was also bombed on 9, 13, and 19 March.[24][27]

Prelude

[edit]Defending force

[edit]

British estimates of the defenders facing the EEF in the region at the beginning of 1917 were no more than 12,000, with the possibility of receiving at most one division as reinforcements.[3]

In early March, Gaza was garrisoned by two battalions, supported by two batteries of Ottoman field artillery. The "Group Tiller" garrison from the Ottoman Fourth Army was later increased to seven battalions.[28][29] The Group consisted of the Ottoman 79th and 125th Infantry Regiments, the 2nd Battalion of the 81st Infantry Regiment, one squadron of cavalry and one company of camelry.[28][29]

Further reinforcements of between 10,000 and 12,000 soldiers were ordered by Kress von Kressenstein as a result of the 300th Flight Detachment's reports of the EEF's advances towards Gaza. Arriving before Eastern Force made its attack, these reinforcements consisted of the 3rd Infantry Division (31st and 32nd Infantry Regiments) from Jemmame, and the 16th Infantry Division (47th and 48th Infantry Regiments) from Tel esh Sheria.[28][29] They were supported by 12 heavy mountain howitzers in two Austrian batteries, two 10-cm long guns in a German battery (from Pasha I) and two Ottoman field artillery batteries.[28][29]

Further, the Ottoman 53rd Infantry Division, which had been garrisoned at Jaffa, was ordered to march south to Gaza, but was not expected before the morning of 27 March. Kress von Kressenstein, the commander of the Ottoman defences, moved his headquarters from Beersheba to Tel esh Sheria where it remained until June.[28][29][30]

However, by 20 March the British considered the Ottoman Army defending Gaza and dominating the coastal route from Egypt to Jaffa, to be "steadily deteriorating."[5] Indeed it had been reported that Kress von Kressenstein complained of "heavy losses" caused by deserters, and between the EEF victory at Rafa in early January and the end of February, 70 deserters had arrived in the EEF lines. These were thought to be a "very small proportion" of the majority of Arabs and Syrians in particular, who disappeared from the Ottoman army, "into the towns and villages of Palestine and Trans-Jordan."[31] The EEF were unaware of the recent Ottoman reinforcements and thought the garrison at Gaza was 2,000 strong.[32] However, by the eve of battle there were probably almost 4,000 rifles defending the town, with up to 50 guns in the surrounding area, while a force of 2,000 rifles garrisoned Beersheba.[33][34][35]

Ottoman Army defences

[edit]

Between Rafa and Gaza, to the east of the coastal sand dunes, a gently rolling plateau of light, firm soil rose slowly inland, crossed by several dry wadis, which became torrential flows in the rainy season. In the spring, after the winter rains, the area was covered by young crops or fresh grass.[36] For millennia, Gaza had been the gateway for invading armies travelling the coastal route, to and from Egypt and the Levant.[7] The town and the fertile surrounding areas strongly favoured defence; Gaza being located on a plateau 200 feet (61 m) high which is separated from the Mediterranean Sea by about 2 miles (3.2 km) of sand hills to the west. To the north, west, and south, orchards surrounded by impenetrable prickly pear hedges extended out for some 3–4 miles (4.8–6.4 km) from the town. With the exception of the ridge extending southwards, which culminated in the dominating 300 feet (91 m) high Ali Muntar, the area of orchards stretched from the high plateau down into a hollow.[37][38]

In addition to these natural defences, the Ottoman Army constructed trenches and redoubts that extended from the south west of the town virtually all the way round the town, except for a gap to the north east. In the process they incorporated Ali Muntar into the town entrenchments by building additional defences on the ridge to the south of the town.[39] Although the trenches were only lightly strengthened with barbed wire, those to the south of Gaza commanded bare slopes which were completely devoid of any cover whatsoever.[40]

Plan of defence

[edit]

As a result of the EEF advance to Rafa and their lengthening of their lines of communication along the coast, flank attacks became a threat. This was because the Ottoman lines of communication further inland overlapped the EEF advance on the coast, and it became important to garrison the region strongly.[41] The EEF right flank would not be in prepared defences, and was potentially vulnerable to an envelopment assault.[42]

Kress von Kressenstein, therefore, deployed most of his defending army away from Gaza to attack the EEF's supply lines. British intelligence thought the defenders would not fight hard for Gaza, because Kress von Kressenstein's plan was to use the 3rd and the 16th Infantry Divisions and the 3rd Cavalry Division to encircle the attacking force and cut the Sinai railway and water pipeline, in the rear of the EEF. A total of 12,000 of the available 16,000 Ottoman soldiers were moving west, to be in position to launch an attack by nightfall on the day of battle.[42]

The main Ottoman force of between two and a half and three divisions, estimated between 6,000 and 16,000 rifles, were deployed at Tel el Negile and Huj with detachments at Tel esh Sheria, Jemmameh, Hareira, Beersheba, and Gaza, to prevent the EEF from out-flanking Gaza.[7][43][44] The rear of the EEF was to be attacked by the Ottoman 16th Division, at a point where the road from Khan Yunis to Gaza crossed the Wadi Ghuzze, and by the Beersheba Group which was to advance via Shellal, to attack Khan Yunis.[28]

Attacking force

[edit]The 22,000-strong attack force consisted of 12,000 infantry and 11,000 mounted troops, supported by between 36 and 96 field guns and 16 howitzers. The mounted units were to stop the Ottoman reinforcements from Tel el Sheria, Jemmameh, Hareira, Negile, Huj, and Beersheba, from reinforcing the Gaza garrison while the infantry captured the town.[37][45][Note 1]

For the attack Dobell deployed Eastern Force as follows:

Desert Column was commanded by Chetwode

- 53rd (Welsh) Division (Major General Alister Grant Dallas)[46]

- 158th (North Wales) Brigade

- 159th (Cheshire) Brigade

- 160th Brigade[Note 2] – less one battalion; plus one section (2 × 60-pounder guns), 10th Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA)[47]

- 53rd Divisional Artillery: 2 Brigades Royal Field Artillery (RFA) (4 batteries each of 4 × 18-pounder guns; 2 batteries each of 4 × 4.5-inch howitzers)[Note 3]

- Anzac Mounted Division (Major General Harry Chauvel) (less 1st Light Horse Brigade)

- 2nd Light Horse Brigade

- New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade

- 22nd Mounted Brigade

- Anzac Mounted Divisional Artillery: 4 Batteries Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) (each of 4 × 18–pdrs = 16 guns)

- Imperial Mounted Division (Major General Henry West Hodgson) (4th Light Horse Brigade not yet formed)

- 3rd Light Horse Brigade

- 5th Mounted Brigade

- 6th Mounted Brigade

- Imperial Mounted Divisional Artillery: 4 Batteries RHA (each of 4 × 18–pdrs = 16 guns)[48][49][50]

- Money's Detachment (Lieutenant Colonel N. Money)

- 2/4th Battalion, Royal West Kent Regiment (160th Brigade, 53rd Division)

- Gloucester Hussars (5th Mounted Brigade, Imperial Mounted Division)

- One section (2 × 60-pdrs), 15th Heavy Battery, RGA.[52]

Eastern Force units under the direct command of Dobell which remained at Rafa, were to protect the lines of communication, the Wadi el Arish crossing, and Khan Yunis, from an attack on the right flank. This force consisted of 8,000 men in the

- 52nd (Lowland) Division (Major General Wilfrid E.B. Smith)[53]

Also under the direct command of Dobell were the

- 54th (East Anglian) Division (Major General Steuart Hare)[56] (less one brigade in the Suez Canal Defences)

- 161st (Essex) Brigade

- 162nd (East Midland) Brigade

- 163rd (Norfolk & Suffolk) Brigade

- 54th Divisional Artillery: 2 Brigades RFA (4 batteries each of 4 × 18–pdrs; 2 batteries each of 4 × 4.5-inch howitzers)[Note 5]

- 74th (Yeomanry) Division

- Army Troops: One 2-gun section from each of 3 RGA Batteries, two of which were detached see above).[48][49][50][60]

The chain of command during the first Battle of Gaza was:

- Murray's Advanced GHQ EEF at El Arish, without reserves; its role was to advise only,

- Dobell's Eastern Force headquarters near In Seirat commanded three infantry divisions, two mounted divisions and a brigade of camels. This force was equivalent to an army of two corps, but only had a staff which was smaller than an army corps serving on the western front,

- Chetwode's Desert Column headquarters also near In Seirat, commanded the equivalent of a corps, with a staff the size of an infantry division.[61]

Lines of communication

[edit]

The Ottoman withdrawal back from Khan Yunis and Shellal, put enough distance between the two forces to require a pause in the advance, while the railway was laid to Rafa.[62] By the end of February 1917, 388 miles (624 km) of railway had been laid (at a rate of 1 kilometre a day), 203 miles (327 km) of metalled road, 86 miles (138 km) of wire and brushwood roads, and 300 miles (480 km) of water pipeline had been constructed.[63] And the Royal Navy undertook to land stores on the beach at Deir el Belah as soon as required and until the railway approached the Wadi Ghazzee.[64]

By 1 March the railhead had reached Sheikh Zowaiid 30 miles (48 km) from Gaza, and by the middle of March the railway had reached Rafa, 12 miles (19 km) from Deir el Belah. Although the Rafa railway station opened on 21 March, it "was not ready for unloading supplies" until after the battle. The railhead was to eventually reached Khan Yunis.[4][41] However, with the arrival of the railway at Rafa, Gaza came within range of an EEF attack by mounted troops and infantry.[25]

Transport

[edit]

With firmer ground the pedrails came off the guns and their teams of eight and ten horses were reduced to six. It also became possible to use wheeled vehicles, and in January the War Office agreed to the infantry divisions being re-equipped with wheeled transport trains. These were to replace camel transport, on the condition that drivers would be found locally, as no transfers from other campaigns were possible. Although camel trains remained important throughout the war, together with pack mules and donkeys, where roads were bad and in hilly trackless terrain, where the horse-drawn and mule-drawn wagons, motor lorries and tractors could not go, they began to be replaced. General service and limber wagons drawn by horses or mules were grouped in supply columns, with the transport wagons of the regiments, the machine–gun squadrons, and the field ambulances, to travel on easier but less direct routes. However, all these animals required vast quantities of food and water, which greatly increased pressure on the lines of communication. During the advance across the Sinai, although it was established that horses did better with two drinks a day instead of three, the volume remained the same.[3][65][66][67][68][69]

Supplying the infantry and mounted divisions was a vast undertaking, as one brigade (and there were six involved in the attack on Gaza) of light horse, mounted rifles, and yeomanry at war establishment consisted of approximately 2,000 soldiers as well as the division of infantry; all requiring food and drink, clothing, ammunition and tools, etc.[70]

Transport was organised, combining the horse-drawn and mule-drawn supply columns with the camel trains, to support Eastern Force operating beyond railhead for about 24 hours.[71][Note 7] "The wagons [of the Anzac Mounted Division] with their teams of mules, two in the pole and three in the lead, [were] driven by one man from the box." These wagons and mules were so successful that the five-mule team was "laid down for the Egyptian Expeditionary Force ... ultimately almost supersed[ing] the British four or six horse ride-and-drive team."[72]

Plan of attack

[edit]

Although Murray delegated the responsibility for the battle to Dobell, he set three objectives. These were to capture a line along the Wadi Ghuzzee in order to cover the laying of the railway line, to prevent the defenders withdrawing before they were attacked, and to "capture Gaza and its garrison by a coup de main."[7] The plan of attack produced by Dobell and his staff, was similar to those successfully implemented at Magdhaba by Chauvel and at Rafa by Chetwode, except that the EEF infantry were to have a prominent role. On a larger scale than the previous battles, the garrison at Gaza, established in fortified entrenchments and redoubts, was to be surrounded and captured, before Ottoman reinforcements could arrive.[44][73][74]

The main attack on the town and Ali Muntar hill would come from the south, by the Desert Column's 53rd (Welsh) Division commanded by Dallas, supported by one infantry brigade of Eastern Force's 54th (East Anglian) Division, commanded by Hare. The Anzac and Imperial Mounted Divisions, commanded by Chauvel and Hodgson respectively, were to establish a screen or cordon around Gaza to the north and east to isolate the garrison, cutting the main roads and preventing an incursion by Ottoman reinforcements reaching the town from their garrisons at Hareira, Beersheba, and Huj. If necessary, the mounted divisions were to be ready to reinforce the infantry attack, while the remaining infantry brigades of the 54th (East Anglian) Division extended the mounted screen to the southeast, just across the Wadi Ghuzzee.[2][74][75]

On 5 March, Murray agreed to Dobell's plan for the attack, which was to be launched at the end of March.[23] On 20 March Dobell moved his headquarters from El Arish to Rafa.[25][37] The next day, the Rafa Race Meeting took place, complete with trophies ordered from Cairo, and a printed programme. These races, complete with an enclosed paddock, totalizator, jumps, and a marked course, were contested by Yeomanry, Australian and New Zealand horses and riders.[58][76] On 22 March, all roads and tracks were reconnoitred as far as Deir el Belah and allotted to the different formations, and preliminary moves towards Gaza were begun.[58]

Dallas' orders were handed to the Anzac, Imperial Mounted, and the 54th (East Anglian) Divisions' commanders at 17:00 on 25 March. The 53rd (Welsh) Division's 158th (North Wales) and 160th Brigades were to begin crossing the Wadi Ghuzzeh at 03:30 and advance up the Burjabye and Es Sire ridges, while the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade which followed the 158th (North Wales) across the wadi, was to remain close to the wadi until further orders were received. Money's Detachment was to cross the wadi mouth and hold a position in the sand dunes between the Rafa-Gaza road and the sea to divert the Ottoman defenders' attention, and cover a section of the 15th Heavy Battery. A section of 91st Heavy Battery was to move into the wadi, while a section the 10th Heavy Battery of 60-pdrs was attached to the 160th Brigade Group. However, artillery ammunition was limited and was to mainly target the Labyrinth group of Ottoman defences. The mounted divisions were to isolate Gaza by stopping the Gaza garrison retiring, or any reinforcements from Huj and Hareira areas, attempting to reinforce Gaza. They were to pursue any hostile force that showed signs of retiring, and if necessary, support the main assault on Gaza, which was to be carried out by the 53rd (Welsh) Division. This division was to be reinforced if necessary by the 161st (Essex) Brigade of the 54th (East Anglian) Division.[77][78][79] At 18:00 Murray, the commander in chief of the EEF, established his headquarters in the carriage of a railway train at El Arish.[61]

Preliminary moves

[edit]On 25 March, the Anzac Mounted Division moved out of their bivouacs in two columns. The first column, consisting of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the 22nd Mounted Yeomanry Brigades, marched up the beach from Bir Abu Shunnar at 02:30, to establish a line just south of the Wadi Ghuzzeh. This advance was to cover reconnaissances of the Wadi Ghuzzeh, which would search for the best places to cross this deep, dry, and formidable obstacle, for both infantry and mounted troops as they advanced towards Gaza.[80][81] The second column, consisting of Anzac Mounted Division's divisional headquarters, Signal Squadron, Field Artillery, and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade (forming divisional reserve), arrived .75 miles (1.21 km) southwest of Deir el Belah. Here the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and the artillery were ordered to water and bivouac at Deir el Belah. By 10:00, Chauvel's Anzac Mounted Division's headquarters and Chetwode's Desert Column headquarters had been established on Hill 310.[82]

While the Ottoman army positions at Gaza had been reconnoitred and photographed from the air, it was still necessary for the staff of the Anzac and Imperial Mounted Divisions, along with the Commander of the Royal Artillery (CRA), to carry out personal reconnaissances of the Wadi Ghuzzeh.[64] By the afternoon all likely crossings had been carefully reconnoitred, and the chosen crossing near the Wadi Sharta, which was to be used the next day, marked.[83]

At 15:30 the Imperial Mounted Division, led by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, marched out of camp at Marakeb, heading for Deir el Belah about six hours or 18 miles (29 km) away. The division's three brigades and their machine gun squadrons were accompanied by their mobile veterinary sections and the 3rd Light Horse Field Ambulance. The troopers carried their day's rations, while rations for 26 and 27 March were to be transported forward during the night of 25/26 March, by the first line transport of camels and wagons. As it had been expected the division would be away five days, additional rations were carried on improvised packs, which accompanied the division as far as Deir el Belah.[58][84]

Approach marches 26 March

[edit]On the day of battle, the 53rd (Welsh) Division, moved out from Deir el Belah at 01:00 in four columns towards El Breij, followed by the artillery. At 02:30 the Anzac Mounted Division left Deir el Belah with the Imperial Mounted Division following at 03:00, heading for the Um Jerrar crossing of the Wadi Ghazze 4.5 miles (7.2 km) east of Deir el Belah.[85] Dallas commanding the infantry established his battle headquarters near El Breij at 03:45, while Chetwode arrived at Desert Column headquarters at In Seirat at 06:37, although he intended to continue moving on to Sheikh Abbas. Dobell commanding Eastern Force arrived from Rafa, at his battle headquarters just north of In Seirat at 06:45.[61]

Fog had begun to develop and from about 03:50 became very thick. It remained for about four hours, then began to lift. Just before dawn at 05:00, it was so dense that objects could not be seen 20 yards (18 m) away, but by this time most of the infantry had crossed the wadi. However, the fog made it impossible for Dallas to reconnoitre the proposed battleground, and he waited at El Breij for it to lift while his two leading brigades moved slowly forward. Visibility was improving about 07:30,[86][Note 8] and by 07:55 the fog had lifted sufficiently for heliographs to be used.[87] However, all aircraft in No. 1 Squadron had to return to their new landing ground at Rafa, as nothing of the ground could be seen from the air.[73] Dallas' 53rd (Welsh) Division was moving forward, despite the fog to make a direct assault on Gaza.[44][88][89] At 05:20, the division's 158th (North Wales) and the 160th infantry brigades were crossing the Wadi Ghuzze while the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade was in reserve. By 06:50 the 160th Brigade had moved towards Shaluf and the 158th (North Wales) Brigade was moving towards Mansura, but they were ordered to slow down because artillery support may not be available, if the fog were to suddenly lift.[90] By 07:50, the leading battalions were approaching Sheikh Seehan without having encountered any Ottoman defenders. Between 08:15 and 08:55 hostile planes flew over the advancing infantry, firing their machine guns into the columns. At 08:30 the 160th (Welsh) Brigade was about 2,400 yards (2,200 m) from Gaza, with their leading battalion 2 miles (3.2 km) southwest of the commanding heights of their main objective, Ali Muntar. The 158th (North Wales) Brigade had reached Mansura,[87][91] and by 09:30 they were three quarters of a mile (1.2 km) north of the 53rd (Welsh) Division's headquarters at Mansura.[90]

Meanwhile, the 54th (East Anglian) Division (less 161st Essex Brigade in Eastern Force reserve) was ordered to cross the Wadi Ghuzzeh immediately after the mounted troops, and take up a position at Sheikh Abbas to cover the rear of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, and keep the corridor open along which it was to attack.[32] The division took up position on Sheikh Abbas Ridge and began digging trenches facing east. The 161st (Essex) Brigade moved to El Burjabye, where it would be able to support either the 53rd (Welsh) Division, or the 54th (East Anglian) Division covering the right rear of the attack, at Sheikh Abbas.[92]

Money's Detachment moved towards the wadi in preparation for crossing at dawn, while the 91st Heavy Battery was covered by the Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry and the divisional cavalry squadron, moved to a position on the Rafa-Gaza road.[93]

Encirclement

[edit]

While the fog made navigation difficult, it also shielded the movement of large bodies of troopers, so the two mounted divisions with the Imperial Camel Brigade attached, rapidly cut the roads leading to Gaza from the north and east, isolating the Ottoman garrison, in a 15 miles (24 km) long cavalry screen.[19][44][55]

The leading division, the Anzac Mounted Division, first encountered hostile forces at 08:00. At that time the 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) was attacked near Sheikh Abbas. Shortly afterwards, hostile aircraft fired machine guns on these leading Desert Column mounted troops. As the mounted screen crossed the Gaza to Beersheba road, they cut the telegraph lines, and a patrol captured ten wagons, while other units captured 30 German pioneers and their pack-horses.[94] At this time, the German commander at Tel esh Sheria, Kress von Kressenstein, received an aerial report describing the advance of two enemy infantry divisions towards Gaza, and about three enemy cavalry divisions and armoured cars, had advanced north between Gaza and Tel esh Sheria. Major Tiller, commanding the Gaza garrison, reported later being attacked from the south, east, and northeast "in great strength." He was ordered to hold Gaza "to the last man."[28]

Soon after 09:00 the 2nd Light Horse Brigade reached Beit Durdis, closely followed by the remainder of their Anzac Mounted Division.[94] At 09:30 four "Officers Patrols" were sent forward towards Huj, Najd 3 miles (4.8 km) north northeast of Huj, Hareira, Tel el Sheria and towards the Ottoman railway line. The headquarters of the Anzac Mounted Division was established at Beit Durdis, and by 10:10 communications by cable with Desert Column, the Imperial Mounted Division, and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade were established. Heliograph stations were also set up and wireless communications established, but the wireless was blocked by a more powerful Ottoman transmitter at Gaza.[87][95] By 10:30, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade had taken up a position (known as Australia Hill) overlooking Gaza from the northeast, and had occupied the village of Jebaliye 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of Gaza. Half an hour later, the 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) was pushing westwards and by 11:30 had reached the Mediterranean coast, to complete the encirclement of Gaza. In the process, this regiment captured the commander of the Ottoman 53rd Division (not to be confused with the 53rd Welsh Division) and his staff, who had been on their way to strengthen the Gaza garrison. At this time, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was concentrated near Beit Durdis, while the 22nd Mounted Brigade formed up south of them. Two squadrons of the 8th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) moved towards Deir Sneid 7 miles (11 km) northeast of Gaza, to watch and wait for the expected approach of reinforcements moving to strengthen Gaza.[96][97]

The Imperial Mounted Division sent patrols towards Hareira, Tel esh Sheria, Kh. Zuheilika and Huj, during their advance to Kh er Reseim where they arrived at 10:00, to connect with the Anzac Mounted Division. Meanwhile, at 09:45, a squadron from the Queen's Own Worcestershire Hussars (5th Mounted Brigade) had encountered hostile units northwest of Kh. el Baha which they charged, capturing 60 prisoners. A further two squadrons of the 5th Mounted Brigade pushed forward towards Kh. el Baha south east of Kh er Reseim, 1 mile (1.6 km) north of the Gaza to Beersheba road, where they remained in support.[95]

The two mounted divisions were now in position, watching for the expected Ottoman reinforcements. By between 11:00 and 11:35, more or less all mounted troops were under fire. This fire came from shells launched from Gaza, or from German or Ottoman planes flying over Beit Durdis, as well as a long range gun, while another gun also fired on the mounted units. The battery of the 5th Mounted Brigade fired on some small groups of Ottoman infantry, but the hostile long range gun accurately returned fire, causing this battery to change position. Very little fighting had yet taken place, so far as the mounted units were concerned, and the infantry attack had not made much progress. However, news was beginning to come in from the overwatching Desert Column patrols, reporting movements from the direction of Huj and the Beersheba railway line, and columns of dust in the direction of Tel esh Sharia, all indicating large scale Ottoman Army movements in progress.[96][98] However, by 12:00 Chetwode commanding Desert Column, had not yet received any reports of Ottoman reinforcements moving towards Gaza, and he sent a message to Chauvel commanding the Anzac Mounted Division and Hodgson commanding the Imperial Mounted Division, to prepare to send a brigade each to assist the infantry attack on Gaza.[99]

The Imperial Camel Brigade crossed the Wadi Ghuzzeh at Tel el Jemmi south of the crossings at Um Jerrar, to reach El Mendur on the bank of the Wadi esh Sheria. Here they established an outpost line between the right of the 5th Mounted Brigade and the Wadi Ghuzzeh.[100] The mobile sections of the field ambulances, followed by their immobile sections and ambulance camel transport, moved towards their outpost positions northeast and east of Gaza.[101][102] With the wadi crossed and strongly defended by the EEF, divisional engineers quickly began to pump water from below the dry bed of the Wadi Ghuzzeh, which was eventually sufficient for all troops engaged. Water was pumped into long rows of temporary canvas troughs for the horses.[93]

Battle

[edit]Infantry attack

[edit]

Gaza was now completely surrounded and, following Desert Column's orders, the 53rd (Welsh) Division, which had not seen action since the Gallipoli campaign, made a direct attack from the south and east towards Ali Muntar. Their 160th Brigade advanced towards Esh Sheluf to get into position by 08:30, with the 158th (North Wales) Brigade advancing towards Mansura, while the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade, which had crossed the wadi by 08:25, had to wait an hour before Dallas ordered them to Mansura to support the 158th Brigade. This delay meant that the 159th could not get into position to take part in the attack until noon.[103] Dallas "had not yet decided" what to do with the 159th. While he met with his brigadiers at the 158th Brigade's headquarters at 10:15, to discuss detailed arrangements of the attack, he was out of communication with Chetwode. This lasted for two hours while his headquarters was moved forward. Dallas contacted Chetwode at 10:50, blaming the delay on the difficulty of bringing the artillery forward, but confirmed he would be ready to launch the attack at 12:00. Due to communication breakdown, Dallas was unaware of the position of the artillery. He had phoned Desert Corps at "10.4" [sic] to be told that the 161st (Essex) Brigade and the 271st RFA were at Sheikh Nebhan. However, they had moved to an exposed position at El Burjabye before finding a covered position in the valley between the Burjabye and Es Sire Ridges. The artillery was in fact already in position and had begun firing at 10:10, although communications had not been established with headquarters.[104] Fog has also been blamed for the delayed infantry attack.[105][106] The artillery bombardment began at 12:00, although there was no artillery program, and the Ottoman defences had not been identified.[107]

Dallas received his orders at 11:00, and half an hour later Dobell and Chetwode ordered him to launch his attack forthwith.[107] By 11:30, Desert Column staff considered that the 53rd (Welsh) Division was practically stationary, and the following message was sent to Dallas: "I am directed to observe that (1) you have been out of touch with Desert Column and your own headquarters for over two hours; (2) no gun registration appears to have been carried out; (3) that time is passing, and that you are still far from your objective; (4) that the Army and Column Commanders are exercised at the loss of time, which is vital; (5) you must keep a general staff officer at your headquarters who can communicate with you immediately; (6) you must launch your attack forthwith." A similar message was sent again at 12:00.[108][Note 9]

Dallas ordered the attack to begin at 11:45 on Ali Muntar by the 160th Brigade which advanced to attack their objective along the Es Sire Ridge, while the 158th (North Wales) which advanced from Mansura, also attacked Ali Muntar. These two infantry brigades had been in position awaiting orders for between three and four hours, while the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade rapidly deployed.[109] They were about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from their objectives with patrols going forward, with the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade (less one battalion), covering their right, advancing to attack the hummock known as Clay Hill. This objective was located to the north of Ali Muntar, on the far side of the Gaza to Beersheba road. The attacking brigades were supported by two field artillery brigades, while a divisional reserve was formed by one battalion of the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade, until the arrival of the 161st (Essex) Brigade (Eastern Force's 54th Division).[107][Note 10] The attacking infantry brigades met with stubborn opposition from determined defenders, firing from strong entrenchments with a clear view of the infantry line of advance, over completely open ground. In these conditions, the attacking infantry's artillery support proved inadequate and a very high number of casualties was suffered.[55][110]

In support, the 54th (East Anglian) Division (less one brigade in Eastern Force reserve) was ordered to cross the Wadi Ghuzzeh immediately after the mounted troops and take up a position at Sheikh Abbas, to cover the rear of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, and keep open the corridor along which the attack was launched.[32] At 11:45 the 161st (Essex) Brigade (54th Division, Eastern Force) was ordered to advance to Mansura in support of the attacking brigades, but the message was apparently never received. At 13:10 an order which had originated from Eastern Force at 12:45 was finally received by hand from a staff officer.[111]

Combined attack

[edit]

By noon, Chetwode was concerned that the strength of the opposition to the infantry attack, could make it impossible to capture Gaza before dark. As a consequence, he ordered Chauvel and Hodgson to reconnoitre towards Gaza, warning them to be prepared to supply one brigade each to reinforce the infantry attack. At 13:00 Chetwode put Chauvel in command of both mounted divisions, and by 14:00 Chauvel was ordering the whole of the Anzac Mounted Division to attack Gaza from the north, while the Imperial Mounted Division and Imperial Camel Brigade, supported by Nos 11 and 12 Light Armoured Motor Batteries and No. 7 Light Car Patrol, were to hold the outpost line and all observation posts. As the Anzac Mounted Division moved north, it was replaced in the mounted screen by the Imperial Mounted Division, which in turn was replaced by the Imperial Camel Brigade.[91][96][98][112]

It took time for the divisions to get into position, and to move Chauvel's headquarters to a knoll between Beit Durdis and Gaza, so he could oversee operations. It was not until during a meeting there at 15:15 that orders were issued for the Anzac Mounted Division's attack.[113] They deployed with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade on a front extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gaza to Jebalieh road, the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade deployed from the Gaza-Jebalieh road to the top of the ridge running northeast, while the Lincolnshire Yeomanry and Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry regiments, of the 22nd Mounted Brigade, held from the right of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade to the track leading to Beit Durdis.[114][115][116]

During this time, the infantry attack on Gaza by the 53rd (Welsh) Division had been progressing. By 13:30, the 160th Brigade on the left had advanced rapidly to capture the Labyrinth, a maze of entrenched gardens due south of Gaza. Their 2/10th Middlesex Regiment established themselves on a grassy hill, while their 1/4th Royal Sussex Regiment advanced up the centre of the Es Sire ridge under intense hostile fire, suffering heavy casualties including their commanding officer. Having reached the crest, they were forced to fall back in some disorder by the Ottoman defenders. However, after being reinforced at 16:00 they recommenced their advance.[117] On the right the 158th (North Wales) Brigade's 1/5th Royal Welsh Fusiliers battalion reached the cactus hedges south of Ali Muntar, where they paused to wait for supporting battalions to come up on their right. Along with the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade, these two brigades slowly fought their way forward towards Clay Hill. Meanwhile, Dallas ordered the 161st (Essex) Brigade of the 54th (East Anglian) Division to capture Green Hill and fill the gap between the 158th (North Wales) and 160th Brigades (53rd Division). By 15:30 the 161st (Essex) Brigade had reached Mansura and they were in a position to launch their attack at 16:00 with the arrival of the 271st Brigade RFA. The fire from this artillery brigade dampened the hostile machine gun fire from Clay Hill, and at 15:50, 45 minutes after the 161st (Essex) Brigade joined the battle, the infantry succeeded in entering the defenders' trenches. They entered at two places to the east of the Ali Muntar mosque, capturing 20 German and Austrian soldiers and another 20 Ottoman soldiers. The 53rd (Welsh) Division reported the successful capture of Clay Hill, located within 600 yards (550 m) of Ali Muntar, at 16:45.[90][118]

Meanwhile the attack by the Anzac Mounted Division, began twenty minutes ahead of schedule at 15:40, before all the patrols had been relieved by the Imperial Mounted Division. The Anzac Mounted Division was supported by the Leicester and Ayrshire artillery batteries, which came into action at ranges of between 3,000 and 4,500 yards (2,700 and 4,100 m) from their targets, respectively.[114] Shortly after the attack began, Chetwode sent messages emphasising the importance of this attack, warning that the trench line northwest of Gaza between El Meshaheran and El Mineh on the sea, was strongly held and offering another brigade from the Imperial Mounted Division, which Chauvel accepted. Hodgson sent the 3rd Light Horse Brigade.[114][119]

At 16:15, five minutes after the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade captured the Clay Hill redoubt near Ali Muntar, the attack on Gaza from the north by the Anzac Mounted Division's 2nd Light Horse Brigade, supported by the Somerset artillery battery, had not been seriously engaged until they reached the cactus hedges. Here they were strongly resisted in close, intense fighting.[90][114][119] The cactus hedges had forced the light horsemen to dismount, however, the assault soon developed and progress was rapid.[38][Note 11] The 2nd Light Horse Brigade was supported by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, which moved forward with the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment in advance, and the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment in support. However, only three troops of the Auckland Mounted Rifle Regiment were in position, the remainder being delayed in the mounted screen, by strong hostile columns of reinforcements advancing from Huj and Nejed.[90][114][119]

At 16:23, the high ridge east of Gaza was captured by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade, while the 22nd Mounted Brigade on their left captured the knoll running west from the ridge.[114] The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's headquarters subsequently took up a position on the ridge, in an area later called "Chaytor's Hill". The Wellington and Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiments pressed on towards Gaza, supported by four machine guns attached to each regiment, the remaining four machine guns being held in reserve.[120] Between 16:30 and 17:00, Ali Muntar was captured by the infantry and the dismounted New Zealanders. The Canterbury Mounted Rifles Regiment had pushed along 'The Ridge' from the rear to assist in the attack, one squadron swinging south against Ali Muntar to enter the defenders' trenches just after the infantry.[55][114][120]

By dusk the light horsemen had reached the northern and western outskirts of the town. The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade's dismounted fighters advanced from Jebaliye against the east and northeast of Gaza to assist in the capture of Ali Muntar, before pushing on through a very enclosed region. This area was intersected with cactus hedges, buildings, and rifle pits occupied by defending riflemen, who strongly resisted the attackers. Despite considerable opposition the New Zealanders continued to slowly advance through the orchards and cactus hedges to the outskirts of the town. During this advance, the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment captured two 77-mm Krupp guns with limbers and ammunition. Shortly afterwards, their progress was stopped by snipers in several houses on the eastern outskirts of the town. The Krupp guns were pushed forward to fire at point blank, blowing up several houses and causing the surrender of 20 hostile soldiers. Meanwhile, the 22nd Mounted Brigade, advancing at the gallop along the track from Beit Durdis to Gaza, had also reached the outskirts of the town by dusk.[119][120][121]

By nightfall, the Anzac Mounted Division had fought their way into the streets of Gaza, suffering very few casualties during this advance. While the attack in the centre by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was progressing, the 22nd Mounted Brigade had come up on the New Zealanders' left, and it was this attacking force that entered the town. Meanwhile, the 2nd Light Horse Brigade had met stiff resistance from defenders holding entrenchments in the sand hills to the northwest of the town. Closest to the Mediterranean coast, the 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) met considerable opposition, but was eventually able to advance close up to the town.[115][121][122]

By 18:00, the position of the attacking force was most satisfactory, and by 18:30 the whole position had been captured, while the defenders were retreating into the town centre. The Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment and the 2nd Light Horse Brigade were well into the northern outskirts of the town. Units of the 158th (North Wales) Brigade (53rd Division) and the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment held Ali Muntar, the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade's right was holding trenches on Clay Hill, while its left was south of the town holding the Gaza to Beersheba road. The 161st (Essex) Brigade (54th Division) held Green Hill and the 160th Brigade (53rd Division) was holding a position to the north of the Labyrinth. By nightfall this combined force was consolidating its captured positions. Only on the western side of Gaza in the sand hills had the attack not been completely successful.[122][123]

Mounted screen attacked

[edit]

At 14:20 Hodgson ordered his Imperial Mounted Division to move north and take over the Anzac Mounted Division's outpost positions. The 6th Mounted Brigade was to move to the east of Beit Durdis, while the 5th Mounted Brigade, currently astride the Gaza to Beersheba road, was to "fill the gap between it and the Camel Brigade," which had orders to move to Kh er Reseim. Owing to a delay in the Camel Brigade receiving its orders, this relief was not completed until two hours later, after 18:30 when the 5th Mounted Brigade moved 2 miles (3.2 km) north.[124]

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Fourth Army's 3rd and 16th Infantry Divisions prepared to launch a counterattack by 1,000 men advancing towards Gaza.[19][125] The two divisions were expected to be in action before dark, but the EEF cavalry and armoured cars were able to stop their advance before they were halfway from Tel esh Sheria to Gaza. Kress von Kressenstein did not persist with the attack but ordered a renewal of their attacks at dawn.[126] About 300 of these reinforcements had been seen at 15:50 (ten minutes after the combined attack on Gaza began) marching towards the town from the north. A little later three more columns were reported moving in the same direction, while another 300 soldiers had moved into the sand hills west of Deir Sineid, to the north of Gaza. A squadron from the 22nd Mounted Yeomanry Brigade was sent to oppose these forces.[114]

From the east, units of the Ottoman Army had first been reported at 14:20, advancing from the direction of Jemmameh (east of Huj).[127] When they were about one point five miles (2.4 km) from Beit Durdis, they attacked the Desert Column outposts holding Hill 405. Two squadrons and one troop of Berkshire Yeomanry (6th Mounted Brigade) defended the front. They reported being attacked by infantry, mounted troops, and some machine gun crews. Hodgson ordered the remainder of brigade, supported by the Berkshire Battery RHA, to reinforce this outpost front line. However, the remainder of the 6th Mounted Brigade was in the process of watering and could not start at once. The delay allowed the Ottoman force to capture the crest of Hill 405 at 17:15.[128][129]

At 17:00, Hodgson commanding the mounted screen, asked Chauvel commanding the mounted attack on Gaza, for reinforcements. Chauvel sent back the 8th and 9th Light Horse Regiments (3rd Light Horse Brigade), commanded by Brigadier General J. R. Royston. They moved back quickly under Royston's command to capture a high hill northwest of Hill 405, which enabled the units of the Berkshire Yeomanry (6th Mounted Brigade) to hold their position. The 8th and 9th Light Horse Regiments (3rd Light Horse Brigade) with the 1/1st Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry (6th Mounted Brigade) held the line, while the 1/1st Nottinghamshire Royal Horse Artillery and the Berkshire Battery enfiladed the advancing hostile formations. Six hostile guns in their firing line, returned fire. When three additional hostile batteries were brought forward, they enfiladed the Berkshire Battery, forcing it to withdraw at about 18:30, just before dusk.[128][129]

After his divisional headquarters moved north, during his take over of the mounted screen, Hodgson discovered that he had lost contact with the 5th Mounted Brigade. It was nearly dark when, at 17:30, a gap occurred in the line between the 6th Mounted Brigade and Imperial Camel Brigade at Kh er Reseim. Fortunately, hostile soldiers did not attempt to investigate the area before Chauvel sent back his last divisional reserve, the 10th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade), to fill the gap. In the growing darkness the light horse regiment succeeded in reaching its position.[124][128]

The No. 7 Light Car Patrol was sent to reinforce units holding off Ottoman reinforcements advancing from Deir Sineid at 17:15. They strengthened the original two squadrons of the 6th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) which held the main road to the north of Gaza. They had been joined by a squadron of the 22nd Mounted Brigade and two more squadrons of the 6th Light Horse Regiment. The Nos. 11 and 12 Light Armoured Motor Batteries (LAMB) also reinforced the mounted screen holding off, about 4,000 Ottoman soldiers advancing from the direction of Huj and Jemmameh. These Ottoman Army units were reported to be 3,000 infantry and two squadrons of cavalry. The LAMBs reported to Royston and engaged the Ottoman Army until dark.[128][130]

Withdrawal of mounted divisions

[edit]

During the battle the serious pressure from Ottoman forces advancing to relieve Gaza from the east had been expected and had begun to make an impact since 16:00. However, in view of the late start to the battle and the threat from these reinforcements, Dobell, the commander of Eastern Force, after talking with Chetwode, the commander of Desert Column, decided that unless Gaza was captured by nightfall, the fighting must stop and the mounted force withdrawn.[131][Note 12] By dusk, some of the strong Ottoman Army trenches and redoubts defending Gaza, remained in their control. The British had fired some 304 shells and 150,000 rounds of small arms ammunition, while their infantry casualties were substantial.[19][132] On the day of battle, 26 March 1917, the sun set at 18:00 (Cairo time). This occurred before Desert Column knew of the capture of Ali Muntar.[133] Therefore, with the approval of Dobell, at 18:10 Chetwode commanding Desert Column, ordered Chauvel to withdraw the mounted force and retire across the Wadi Ghuzzeh. As these orders were being dispatched, a report came in from Dallas that Ali Muntar had been captured, but this information did not change Chetwode's mind. It was not until some time later that he was informed of the capture of the entire ridge.[133] Chetwode's orders were to break off the action after dark and withdraw.[55][122][134]

According to Christopher Pugsley, the Anzac Mounted Division "saw victory snatched away from them by the order to withdraw."[81][Note 13] This decision to withdraw was puzzling to many of those fighting in and near the town, as the infantry held Ali Muntar and 462 German and Ottoman army prisoners, including a general who was a divisional commander. They had also captured an Austrian battery of two Krupp 77 mm field guns, along with a complete convoy.[105][132][135] However, the whole attacking force was withdrawn to Deir el Belah and Khan Yunus on 27 and 28 March.[136][137] The first units to withdraw were the slow moving wheels and camels, which received their orders at 17:00 from Desert Column. They move back to Hill 310 via Sheikh Abbas.[90][128] With the Imperial Mounted Division, remaining in position to cover the retirement of the Anzac Mounted Division, the withdrawal of the fighting mounted units was slow and difficult, not because of hostile pressure (there was none until dawn), but because the units were intermixed and the dismounted troops were far from their horses. One unit, the 7th Light Horse Regiment (2nd Light Horse Brigade) was nearly 4 miles (6.4 km) from their horses and all their wounded had not yet been collected.[138] The No. 7 Light Car Patrol reported to the headquarters of the Anzac Mounted Division at 18:40 and was ordered to return to base, while the cars of the Nos. 11 and 12 LAMB, camped in the vicinity of Kh er Reseim. At 19:05 Anzac Mounted Division's artillery began its retirement from divisional headquarters under escort, and the 43 wounded from the Anzac Mounted Division and 37 wounded from Imperial Mounted Division were collected and brought to the ambulances, while prisoners were sent back under escort. By 19:30 the 22nd Mounted Brigade was moving toward Divisional Headquarters and the 6th Mounted Brigade withdrew while Ottoman soldiers dug in on Hill 405.[89][128][139]

At about midnight the Anzac Mounted Division was clear of the battlefield, while the Imperial Mounted Division, with the assistance of the Imperial Camel Brigade and armoured motor cars, held off the Ottoman reinforcements.[128][136] At 02:00 when the guns of Anzac Mounted Division had reached Dier el Belah and the division was just passed Beit Dundis, Hodgson gave orders for the concentration of the Imperial Mounted Division's 3rd Light Horse, 5th, and 6th Mounted Brigades, while the Imperial Camel Brigade took up a line from the Wadi Guzzeh to the left of the 54th (East Anglian) Division's headquarters.[138][140]

At 04:30, the cars in the Nos. 11 and 12 LAMB broke camp near Kh er Reseim, and as they moved southwards encountered opposition from Ottoman Army units. After two hours of stiff fighting they managed to retire, while at 04:50 the No. 7 Light Car Patrol was moving along the Gaza to Beersheba road. It was not until 05:30 that an Ottoman attack in strength fell on the rear of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade (Imperial Mounted Division) just as the brigade was crossing the Gaza-Beersheba road near Kh Sihan. The No. 7 Light Car Patrol gave very effective support to the brigade, and together with the light horsemen, became heavily engaged, fighting the Ottoman Army advancing from Huj. The advancing reinforcements were stopped, and the light cars covered the 3rd Light Horse Brigade's retirement back to the Imperial Camel Brigade's position, at 07:00 on the morning of 27 March 1917.[132][138][Note 14]

I wish to draw special attention to the excellent service rendered by the Imperial Mtd Div under Major General H.W. Hodgson CB CVO, in holding off greatly superior forces of the enemy during the afternoon of the 26th and the night of 26/27th thus enabling the A & NZ Mtd Div to assist in the Infantry attack on Gaza and subsequently to withdraw after dark. Had the work of this Division been less efficiently carried out it would have been quite impossible to extricate the A & NZ Mtd Div without very serious losses.

— Chauvel commanding Anzac Mounted Division, Account of Operations dated 4 April 1917[132]

Withdrawal of infantry

[edit]At 17:38 Dobell commanding Eastern Force, ordered the 54th (East Anglian) Division to move 2 miles (3.2 km) to the west to Burjabye Ridge, and informed Desert Column. An hour later, at 18:35 (25 minutes after Chetwode ordered Chauvel to withdraw), Dobell informed Desert Column and the 54th (East Anglian) Division "that he contemplated withdrawing the whole force across the Wadi Ghazze if Gaza did not shortly fall."[141]

There have been claims that the infantry were the first to retire and that, due to a communications breakdown, the 53rd (Welsh) Division made a complete and premature retirement.[142][143] However, that infantry division had not been told of the movement of the 54th (East Anglian) Division and was still in position. It was not until just before 19:00 that Chetwode phoned Dallas, commander of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, to inform him of the withdrawal of the mounted troops, and the need for him to move his right to reestablish contact with the 54th (East Anglian) Division. Dallas was under the impression that he was to move back to Sheikh Abbas, 4 miles (6.4 km) from his right on Clay Hill, while Chetwode meant that the two divisions would reconnect 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Mansura and not much over 1 mile (1.6 km) from the 161st (Essex) Brigade, 54th (East Anglian) Division, at Green Hill. Dallas protested, instead asking for reinforcements to close the gap between the two divisions. This request was denied and when he prevaricated, asking for time to consider the order, Chetwode gave him the verbal order, believing the 53rd (Welsh) Division was moving its right back to gain touch with the 54th (East Anglian) Division near Mansura.[141] Falls notes that according to Dallas "he had explained on the telephone the full extent of his withdrawal to General Chetwode; the latter states that he did not understand his subordinate to mean that he was abandoning anything like so much ground. In any case the responsibility rests upon Desert Column Headquarters, since General Dallas had telegraphed to it the line he was taking up."[144]

As late as 21:12, the 53rd (Welsh) Division still held Ali Muntar, at which time they advised Desert Column they would have to evacuate towards Sheikh Abbas, to conform with a withdrawal occurring on their right.[90][128] At 22:30 Dallas, commander of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, issued orders for the whole of his force to withdraw to a line which stretched from the caves at Tell el Ujul, near the Wadi Ghuzzeh on the left through a point 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Esh Sheluf, and on to Mansura and Sheikh Abbas involving a retirement of 1 mile (1.6 km) on the Es Sire Ridge and 3 miles (4.8 km) between Clay Hill and Mansura. He informed Desert Column of this move.[145] By 23:00, Dobell commanding Eastern Force, had become aware of the extent of the 53rd (Welsh) Division's successes. He also received intercepted wireless messages, which had been unduly delayed, between Kress von Kressenstein at Tel esh Sheria and Major Tiller, the German officer commanding the Gaza garrison, indicating the desperate situation of the garrison. Dobell immediately ordered Chetwode and Dallas to dig in on their present line, connecting his right with the 54th (East Anglian) Division.[146]

Reoccupations and retreats

[edit]It was nearly midnight when Dallas commanding 53rd (Welsh) Division, discovered the 54th (East Anglian) Division was moving towards the north of Mansura – had he known of this move at the time, he would not have abandoned all of the captured positions.[145] At 05:00 on 27 March, when Chetwode learned that the 53rd (Welsh) Division had abandoned its entire position, and he ordered them back to Ali Muntar. Dallas ordered the 160th Brigade (53rd Division) and 161st (Essex) Brigades (54th Division) to push forward with strong patrols to the positions they had held on the previous evening. Both Green Hill and Ali Muntar were found to be unoccupied and one company of the 1/7th Battalion Essex Regiment, (161st Brigade) reoccupied Ali Muntar, while two companies of the same battalion reoccupied Green Hill. After the 2nd Battalion of the 10th Middlesex Regiment (160th Brigade) had pushed forward patrols beyond Sheluf, the 2nd Battalion of the 4th Royal West Surrey or 4th Royal West Kent Regiment (160th Brigade) was ordered to advance and "gain touch" with the 161st Brigade. However, as the battalion advanced in artillery formation, they could see the 161st Brigade to the northeast "falling back." Meanwhile the 1/1st Battalion, Herefordshire Regiment (158th Brigade, 53rd Division) had also been ordered to reoccupy their brigade's position and was advancing, when they too saw the 161st Brigade withdrawing.[147][148]

After dawn on 27 March the first Ottoman counterattacks recaptured Ali Muntar and a portion of Green Hill, but the 1/7th Battalion of the Essex Regiment, (161st Brigade, 54th Division), retook the positions before consolidating and re-establishing their posts. Meanwhile, the Ottoman force, which had attacked the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, appeared on Sheikh Abbas and shelled the rear of Dallas' position, "including his reserves, medical units and transport camels," but made no serious attack on the 54th (East Anglian) Division holding Burjabye Ridge.[149] The hostile artillery batteries at Sheikh Abbas targeted all the tracks across the Wadi Ghuzzeh, employed by the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps, who were at the time attempting to supply food, water and ammunition, to the forward units.[150] At 08:00 the 53rd (Welsh) Division came under orders of Eastern Force, and Dobell received an appreciation from Dallas at 09:15. This stated that if the present positions of the 53rd (Welsh) and 54th (East Anglian) Divisions were to be maintained, the German and Ottoman occupation of Sheikh Abbas must be ended. This was confirmed by G. P. Dawnay, Brigadier General General Staff (BGGS), Eastern Force. Dallas suggested Sheikh Abbas might best be recaptured by Desert Column, as the 52nd (Lowland) Division was too far away.[151]

However, by 08:10 the Imperial Mounted Division had arrived back at Deir el Belah and the Anzac Mounted Division was marching via Abu Thirig past Hill 310 where Chauvel met Chetwode. Chetwode ordered the horses of both divisions to water and return to a position near El Dameita to support an attempt by the infantry to retake Ali Muntar. At 08:30 when the Anzac Mounted Division also arrived back at Deir el Belah, Chetwode took over command of the two mounted divisions from Chauvel.[132] The Anzac Mounted Division returned to take up a position near El Dameita which it held until 16:00, while the 54th (East Anglian) Division remained near Sheikh Abbas engaging the advancing Ottoman units from Beersheba.[132][142]

Ali Muntar, which had been held by two battalions of the Essex Regiment (54th Division), was strongly attacked, and at 09:30 the British infantry were forced to withdraw, having suffered severe losses. They fell back to Green Hill where they were almost surrounded, but managed to withdraw to a line south of Ali Muntar halfway between that hill and Sheluf.[151] After first advising Murray, at 16:30 Dobell issued orders for the withdrawal to the left bank of the Wadi Ghuzzeh of the 53rd (Welsh) and the 54th (East Anglian) Divisions under the command of Dallas. This retirement, which began at 19:00, was completed without interference from the Ottoman Army.[150] An aerial reconnaissance on the morning of 28 March reported that no Ottoman units were within range of the British guns.[152] No large scale attacks were launched by either side, but very active aircraft bombings and artillery duels continued for a time.[153]

Casualties

[edit]

British casualties amounted to 4,000; 523 killed, 2932 wounded and over 512 missing, including five officers and 241 other ranks known to be prisoners. These were mainly from the 53rd (Welsh) Division and the 161st (Essex) Brigade of the 54th (East Anglian) Division. The Ottoman Army forces suffered a total of 2,447 casualties. Of these, 16 Germans and Austrians were killed or wounded, 41 being reported missing, and 1,370 Ottoman soldiers were killed or wounded with 1,020 missing.[154] According to Cemal Pasha, Ottoman losses amounted to fewer than 300 men killed, 750 wounded, and 600 missing.[155] The Anzac Mounted Division suffered six killed, 43 or 46 wounded, and two missing, while the Imperial Mounted Division suffered 37 casualties.[132][137]

Aftermath

[edit]Both Murray and Dobell portrayed the battle as a success, Murray sending the following message to the War Office on 28 March: "We have advanced our troops a distance of fifteen miles from Rafa to the Wadi Ghuzzee, five miles west of Gaza, to cover the construction of the railway. On the 26th and 27th we were heavily engaged east of Gaza with a force of about 20,000 of the enemy. We inflicted very heavy losses upon him ... All troops behaved splendidly."[156] And Dobell wrote,

This action has had the result of bringing the enemy to battle, and he will now undoubtedly stand with all his available force in order to fight us when we are prepared to attack. It has also given our troops an opportunity of displaying the splendid fighting qualities they possess. So far as all ranks of the troops engaged were concerned, it was a brilliant victory, and had the early part of the day been normal victory would have been secured. Two more hours of daylight would have sufficed to finish the work the troops so magnificently executed after a period of severe hardship and long marches, and in the face of most stubborn resistance.

— General Dobell, Eastern Force[156]

The British press reported the battle as a success, but an Ottoman plane dropped a message that said, "You beat us at communiqués, but we beat you at Gaza."[157] Dallas, the commander of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, resigned after the battle, owing to a "breakdown in health."[158] Judged by Western Front standards, the defeat was small and not very costly. Murray's offensive power had not been greatly affected and preparations for a renewal of the offensive were quickly begun. The Second Battle of Gaza began on 17 April 1917.[159]

A report in the Daily Telegraph said on 26 March that British troops were severely delayed until early afternoon by a dense morning fog, during which delay they drank much of their water rations, leaving the men short of water; and that the main aim was to seize the Wadi Ghuzzeh to cover the advance of a supply railway which the British were building.[160]

Notes

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ The numbers of British troops involved are approximate only. One instance of a report telegraphed to Britain stated a division's strength at about 9,000 "when its battalions were only 400 strong in action." [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 p. ix]

- ^ The 160th had originally been the Welsh Border Brigade, but had been broken up in 1914 and reconstituted with battalions from Home Counties regiments.[Becke; Dudley Ward, pp. 12–4.]

- ^ One RFA brigade was absent from each of 53rd and 54th Divisions, and the 18-pdr batteries only had four of their six guns. [MacMunn & Falls, pp. 285, 304.]

- ^ Although listed under Dobell's direct command, [Wavell 1968, pp. 92–4, Powles 1922, pp. 84, 278–9, Preston 1921, p. 331–3] these cars assisted Desert Column hold off the approaching Ottoman reinforcements. [Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 301]

- ^ See 53rd Divisional Artillery

- ^ The ICB battalions have also been described in an April 1917 Order of Battle as the 1st (Australian and New Zealand), the 2nd (Imperial) and the 3rd (Australian and New Zealand) battalions. [Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 397]

- ^ Falls notes there was insufficient transport to support operations at any considerable distance from railhead and while the infantry had wheeled transport the mounted divisions still had camel transport. [Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 280]

- ^ There are varying accounts of exactly when the fog lifted from 07:00 to 11:00. [Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 290 note]

- ^ There is no mention of any units of the 53rd (Welsh) Division in Desert Column's War Diary between 09:30 when the division established headquarters at Mansura and 13:10, when the 159th (Cheshire) Brigade came into action beside the 158th (North Wales) Brigade. [Desert Column War Diary March 1917 AWM4-1-64-3 Part 1-1]

- ^ It has been claimed that at 10:15 the commander of 53rd (Welsh) Division ordered the attack on Gaza and fifteen minutes later the attack commenced. [Hill 1978 pp. 103–4, 22nd Mounted Brigade Headquarters War Diary AWM4–9–2–1 Part 1]

- ^ While fighting on foot, one quarter of a light horse and mounted rifle brigade were holding the horses. A brigade was then equivalent in rifle strength to an infantry battalion. [Preston 1921 p. 168]

- ^ It is claimed that the need to water the horses was "constantly on their minds." The horses had been watered as they crossed the Wadi Ghuzzee and small quantities had been found by the mounted divisions and reported to headquarters during the day.[Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 305]

- ^ The Australian history claims Chauvel protested strongly. [Gullett 1941 p. 282] While the British history notes no written record of Chauvel's protest is "on the record." [Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 307 note]

- ^ Lieutenant McKenzie commander of No. 7 Light Car Patrol gives a description of making full use of the patrol's capabilities during their retirement. [Gullett 1941 pp. 288–9 and Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 308]

- Citations

- ^ Falls 1930. Vol. 1 p. 272

- ^ a b c d Bruce 2002, pp. 92–3

- ^ a b c d e Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 273

- ^ a b Falls 1930. Vol. 1 p. 279.

- ^ a b c Woodward 2006, p. 68–9

- ^ a b c Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 276

- ^ a b c d Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 281

- ^ a b c McPherson 1985 pp. 172–3

- ^ a b Secret Military Handbrook 23 January 1917 Supplies pp. 38–49 Water pp. 50–3 Notes pp. 54–5

- ^ a b Moore 1920 p. 68

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 1 pp. 272, 278

- ^ Bruce 2002 p. 88

- ^ Bou 2009, pp. 162–3

- ^ Imperial Mounted Division War Diary AWM4-1-56-1 Part 1

- ^ 3rd Light Horse Brigade War Diary AWM4-10-3-26

- ^ Bruce 2002, p. 90

- ^ Carver 2003, pp. 196–7

- ^ Powles 1922, p. 82

- ^ a b c d Erickson 2001, p. 161

- ^ Powles 1922, pp. 83–4

- ^ Keogh 1955, pp. 78–9

- ^ Bruce 2002, pp. 90–1

- ^ a b c Downes 1938, p. 616

- ^ a b Falls 1930 Vol. 1 pp. 277–8

- ^ a b c Blenkinsop 1925 p. 184

- ^ Bruce 2002 p. 87

- ^ Cutlack 1941, pp. 56–9

- ^ a b c d e f g Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 321 note 1

- ^ a b c d e Erickson 2007 pp. 99–100

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 57 note

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 277 and note

- ^ a b c Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 285

- ^ Bruce 2002, p. 93

- ^ Gullett 1941, pp. 253–254

- ^ Keogh 1955, p. 84

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 1 pp. 281–2

- ^ a b c Downes 1938, p. 618

- ^ a b Powles 1922, p. 91

- ^ Anzac Mounted Division War Diary March 1917 Appendix No. 54 Sketch Map showing position of attacking infantry and mounted divisions at about 09:30 on 25 March 1917.

- ^ a b Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 283

- ^ a b Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 280

- ^ a b Erickson 2007, p. 100

- ^ a b Keogh 1955, p. 83

- ^ a b c d Bruce 2002, p. 92

- ^ Gullett 1941 p. 265

- ^ Becke, pp. 117–23.

- ^ MacMunn & Falls, p. 286.

- ^ a b Wavell 1968, pp. 92–4

- ^ a b Powles 1922, pp. 84, 278–9

- ^ a b Preston 1921, p. 331–3

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 301

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 1 p. 285 note3

- ^ Becke, pp. 109–15.

- ^ Bruce 2002, pp. 93, 95

- ^ a b c d e Blenkinsop 1925 p. 185

- ^ Becke, pp. 125–31.

- ^ "Imperial Camel Corps". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d Powles 1922, p. 84

- ^ Wavell 1968, pp. 92–3

- ^ MacMunn & Falls, pp. 285–8, 304.